H5N1 Alert US Speeds Up Bird Flu Vaccine Development

H5n1 alert us health department accelerates new bird flu vaccine development amid pandemic scare – H5N1 alert! The US health department is accelerating the development of a new bird flu vaccine amid growing pandemic fears. This isn’t just another headline; it’s a race against time, a testament to the potential devastation of a highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak. We’re diving deep into the science, the strategy, and the very real anxieties surrounding this rapidly evolving situation.

Get ready to learn about the H5N1 virus, the vaccine development process, and what you can do to protect yourself and your community.

This post explores the characteristics of the H5N1 virus, its transmission, and its history. We’ll examine the US government’s response, including the accelerated vaccine development and distribution strategies. We’ll also discuss the economic and social implications of a potential pandemic, as well as the ethical considerations surrounding vaccine allocation. It’s a complex issue with far-reaching consequences, and understanding it is crucial.

H5N1 Virus

Source: yimg.com

The highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus, commonly known as bird flu, represents a significant zoonotic threat, capable of spreading from birds to humans. Understanding its characteristics, historical impact, and differences from other influenza strains is crucial for effective public health preparedness.

H5N1 Virus Characteristics and Transmission

H5N1 is a subtype of influenza A virus, characterized by its high pathogenicity in birds. Transmission to humans primarily occurs through direct contact with infected birds (live or dead), their droppings, or contaminated surfaces. The virus can also spread through airborne droplets, though this mode of human-to-human transmission remains relatively inefficient compared to other influenza strains. The severity of infection in humans varies considerably, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe pneumonia and death.

The H5N1 bird flu scare has everyone on edge, with the US health department racing to develop a new vaccine. It makes you think about the future, and the importance of planning, even amidst uncertainty. For example, I recently read about Karishma Mehta’s decision to freeze her eggs, and the article karishma mehta gets her eggs frozen know risks associated with egg-freezing really highlighted the complexities involved.

Ultimately, both situations underscore the need to prepare for the unexpected, whether it’s a pandemic or personal life choices. The urgency surrounding the H5N1 vaccine development feels very real right now.

Historical Impact of H5N1 Outbreaks, H5n1 alert us health department accelerates new bird flu vaccine development amid pandemic scare

H5N1 outbreaks have been reported globally since the late 1990s, with significant impacts on poultry populations and human health. The virus has caused substantial economic losses due to culling of infected birds and trade restrictions. Mortality rates in humans infected with H5N1 have historically been high, often exceeding 50%, although this figure varies depending on factors such as access to medical care and the specific strain involved.

Regions in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa have been particularly affected by outbreaks. The 2004-2006 outbreak, for example, highlighted the virus’s potential to spread across continents and cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Comparison of H5N1 with Other Influenza Strains

Compared to seasonal influenza strains (like H1N1 and H3N2), H5N1 exhibits significantly higher pathogenicity in humans. While seasonal influenza typically causes mild to moderate illness, H5N1 infections are frequently severe and life-threatening. The unique genetic characteristics of H5N1, particularly its hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins, contribute to its ability to evade the immune system and cause more severe disease.

The H5N1 bird flu scare has everyone on edge, with the health department racing to develop a new vaccine. It’s a reminder that unexpected health crises can impact us all, highlighting the importance of understanding how to manage existing conditions effectively, like learning about strategies to manage Tourette Syndrome in children , which requires proactive approaches. This focus on preparedness, whether for a pandemic or a chronic condition, underscores the need for constant vigilance and planning.

The potential for H5N1 to mutate and acquire the ability for efficient human-to-human transmission represents a major concern for global pandemic preparedness. Unlike seasonal influenza, which circulates annually, H5N1 outbreaks tend to be more sporadic and geographically localized.

Symptoms of H5N1 Infection in Humans

The symptoms of H5N1 infection can vary significantly in severity. Early symptoms are often similar to those of seasonal influenza, but can rapidly progress to more severe complications.

| Mild Symptoms | Moderate Symptoms | Severe Symptoms | Critical Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | Cough | Severe pneumonia | Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) |

| Sore throat | Muscle aches | Respiratory failure | Multiple organ failure |

| Headache | Fatigue | High fever (above 104°F) | Death |

| Runny nose | Diarrhea | Severe dehydration |

US Health Department Response

Source: ytimg.com

The emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) viruses capable of infecting humans has understandably raised significant concerns globally. The US health department, primarily through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has initiated a multi-pronged strategy to mitigate the potential threat of a pandemic. This involves surveillance, preparedness measures, and crucially, the accelerated development of effective vaccines.The current strategy focuses on a proactive approach, recognizing that swift action is crucial in containing any potential outbreak.

This proactive stance involves not only vaccine development but also strengthening public health infrastructure, improving diagnostic capabilities, and enhancing communication strategies to inform and protect the public.

Accelerated Vaccine Development Process

The development of an H5N1 vaccine is being fast-tracked, utilizing advanced technologies and streamlining regulatory processes. This accelerated process involves several key stages, typically including pre-clinical testing (in vitro and animal studies), clinical trials (Phase 1, 2, and 3), and finally, regulatory review and approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While timelines vary depending on the specific vaccine and the results of each stage, the goal is to significantly reduce the time normally required, aiming for a much faster path to vaccine availability compared to traditional vaccine development processes.

For example, during the initial stages of the COVID-19 vaccine development, the process was remarkably sped up by parallel processing of the different phases and by utilizing previously acquired knowledge and data.

Vaccine Types and Effectiveness

Several types of H5N1 vaccines are under development. These include inactivated vaccines, which use killed virus particles, and potentially live attenuated vaccines, which use weakened versions of the virus. The choice of vaccine type depends on factors such as safety, efficacy, and production scalability. The effectiveness of any vaccine will depend on several factors, including the specific strain of the virus, the individual’s immune response, and the vaccine’s formulation.

Historically, influenza vaccines have shown varying degrees of effectiveness, ranging from 40% to 60% in preventing infection, but often higher in preventing severe illness and hospitalization. Extensive clinical trials are essential to determine the actual effectiveness of any new H5N1 vaccine against different circulating strains.

Vaccine Development and Distribution Flowchart

The following illustrates the simplified process:[Imagine a flowchart here. The flowchart would begin with “Virus Identification and Characterization.” This would flow to “Vaccine Candidate Selection.” Then to “Pre-clinical Testing (animal models).” Following this would be “Phase 1 Clinical Trials (safety and dosage).” Next would be “Phase 2 Clinical Trials (efficacy and immunogenicity).” This is followed by “Phase 3 Clinical Trials (large-scale efficacy and safety).” The next step would be “FDA Review and Approval.” Finally, the process ends with “Vaccine Manufacturing and Distribution.”]The flowchart visually depicts the sequential nature of vaccine development and the crucial role of each stage in ensuring the safety and efficacy of the final product.

Each stage involves rigorous testing and data analysis, before proceeding to the next. Efficient manufacturing and a robust distribution network are also vital to ensure timely access to the vaccine for the population.

Pandemic Preparedness and Public Health Measures

Source: nature.com

The emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) viruses capable of infecting humans necessitates robust pandemic preparedness strategies. A multi-pronged approach, encompassing surveillance, rapid response, and public health communication, is crucial to mitigate the impact of a potential pandemic. The US, along with other nations, has learned valuable lessons from past influenza outbreaks, informing current strategies and emphasizing the importance of proactive measures.

The US government’s response to potential H5N1 outbreaks relies heavily on a layered approach to public health. This involves proactive surveillance, rapid diagnostic capabilities, and the implementation of control measures to limit the spread of the virus. These measures are designed to minimize human-to-human transmission, a key factor in determining the severity of any pandemic.

Early Detection and Surveillance Systems

Effective surveillance is the cornerstone of pandemic preparedness. The US utilizes a sophisticated network of laboratories, veterinary services, and public health agencies to monitor avian influenza activity in poultry and wildlife populations. Early detection of outbreaks in birds allows for rapid implementation of control measures, such as culling infected flocks and implementing biosecurity measures on farms, minimizing the risk of human exposure.

This system also includes enhanced monitoring of human cases, utilizing rapid diagnostic tests to quickly identify and isolate infected individuals, thus preventing further spread. The speed and accuracy of detection directly impact the effectiveness of containment efforts. For example, the rapid identification of the H1N1 virus in 2009 allowed for swift implementation of public health measures, limiting the severity of the pandemic compared to previous outbreaks.

Comparison of Public Health Strategies in Past Influenza Pandemics

Past influenza pandemics, such as the 1918 Spanish Flu and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, have provided valuable insights into effective public health strategies. The 1918 pandemic, characterized by its high mortality rate, highlighted the limitations of public health infrastructure at the time. In contrast, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic saw a more coordinated global response, leveraging advancements in virology, diagnostics, and communication technologies.

While both pandemics involved social distancing measures, the 2009 response benefited from improved understanding of virus transmission and the availability of antiviral medications. The key difference lies in the technological advancements and coordinated international collaboration that enhanced the response to the 2009 pandemic. Lessons learned from both events emphasize the importance of robust surveillance systems, rapid response mechanisms, and international collaboration.

Recommendations for Reducing H5N1 Infection Risk

It is vital for individuals to take proactive steps to minimize their risk of H5N1 infection. While human-to-human transmission remains relatively rare, preventative measures are crucial, particularly for individuals at high risk.

The following recommendations can significantly reduce the likelihood of infection:

- Avoid contact with poultry, particularly sick or dead birds.

- Practice thorough hand hygiene with soap and water, especially after handling poultry or potentially contaminated surfaces.

- Cook poultry thoroughly to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) to kill the virus.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Stay informed about public health advisories and follow recommendations from health officials.

- If you experience flu-like symptoms after contact with poultry or potentially contaminated environments, seek medical attention immediately.

Economic and Social Impacts of an H5N1 Pandemic

The potential for a widespread H5N1 avian influenza pandemic poses a significant threat not only to public health but also to the global and US economy and social fabric. The scale of disruption would depend on several factors, including the virus’s transmissibility, severity, and the effectiveness of public health interventions. However, even a moderate pandemic could trigger cascading economic and social consequences, far exceeding the costs of preparedness and response.

Economic Consequences of a Widespread H5N1 Outbreak in the US

A major H5N1 pandemic would severely impact the US economy across multiple sectors. Reduced workforce participation due to illness, quarantine measures, and fear would cripple productivity. Supply chains would be disrupted, leading to shortages of essential goods and services. Increased healthcare costs, coupled with decreased consumer spending and investment, would lead to a significant economic downturn. The 2008-2009 H1N1 pandemic, while less severe than a potential H5N1 pandemic, resulted in billions of dollars in lost productivity and healthcare costs, providing a glimpse into the potential scale of economic damage.

The H5N1 bird flu scare has understandably spurred our health department into overdrive, accelerating the development of a new vaccine. Maintaining a strong immune system is crucial during such times, and that got me thinking about nutrition; I recently read an interesting article exploring how diet impacts immunity, specifically, are women and men receptive of different types of food and game changing superfoods for women , which highlights the importance of tailored nutrition.

Knowing what fuels our bodies best could be as vital as a vaccine in fighting this pandemic threat.

The severity of an H5N1 pandemic could dwarf these figures, potentially triggering a global recession.

Social Disruptions and Impacts on Healthcare Systems

The social disruption caused by an H5N1 pandemic would be profound. Healthcare systems would be overwhelmed, leading to rationing of care and potentially increased mortality rates. Schools and businesses would likely close, disrupting education and employment. Social distancing measures and quarantine protocols would limit social interaction and severely impact daily life. Fear and uncertainty would spread rapidly, potentially leading to social unrest and civil disorder.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, for instance, led to widespread social disruption, including labor shortages, food shortages, and social isolation, highlighting the profound social impact of a pandemic.

Examples from Previous Pandemics

The 1918 influenza pandemic dramatically illustrates the devastating economic and social consequences of a global pandemic. It resulted in significant economic losses due to reduced productivity, widespread illness, and high mortality rates. Beyond the direct economic costs, the pandemic led to widespread social disruption, including labor shortages, food shortages, and social unrest. The impact of the 1918 pandemic on global trade and economic activity was immense.

Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic showcased the fragility of global supply chains and the profound social and economic consequences of widespread illness and lockdown measures. The economic losses associated with COVID-19, including business closures, job losses, and healthcare costs, were substantial, serving as a sobering reminder of the potential impact of future pandemics.

Potential Economic Impact on Various Sectors

| Sector | Potential Impact | Example | Potential Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Reduced production, labor shortages, disruptions to supply chains | Poultry farms forced to cull flocks, impacting meat supply | Government subsidies, diversification of supply chains |

| Tourism | Significant decline in travel and tourism, loss of revenue | Travel restrictions, fear of infection deterring tourists | Government support packages, public health messaging |

| Healthcare | Overwhelmed healthcare systems, increased costs, shortages of medical personnel | Hospitals reaching capacity, shortages of ventilators and beds | Increased healthcare capacity, surge planning, public health education |

| Manufacturing | Disrupted supply chains, reduced production, labor shortages | Factory closures due to illness, difficulty sourcing raw materials | Diversification of supply chains, government support for businesses |

Ethical Considerations and Vaccine Distribution

The rapid development of an H5N1 vaccine in response to a potential pandemic raises crucial ethical questions surrounding its distribution and prioritization. Ensuring fair and equitable access is paramount, particularly given the potential for severe illness and mortality associated with this virus. Transparency and public trust are essential for successful vaccine rollout and acceptance. Mismanagement of vaccine allocation can lead to distrust in public health institutions, hindering efforts to control the pandemic.

Ethical challenges arise from the inherent scarcity of vaccines during the initial phases of a pandemic. Limited production capacity means difficult choices must be made about who receives the vaccine first. Prioritization strategies must balance competing ethical principles such as maximizing benefits, minimizing harm, and promoting fairness. Open and honest communication about these decisions is vital for maintaining public trust and ensuring the legitimacy of the vaccination program.

Strategies for Equitable Vaccine Access

Equitable access to an H5N1 vaccine necessitates a multi-pronged approach. This includes prioritizing vulnerable populations, ensuring geographic accessibility, and addressing potential inequities based on socioeconomic status, race, and other factors. Transparency in the decision-making process is key to building public confidence. International collaboration is also crucial, especially in ensuring equitable distribution across countries with varying levels of resources and healthcare infrastructure.

Strategies such as tiered vaccine allocation, based on risk factors, and the implementation of robust monitoring systems to track vaccine distribution and effectiveness, are vital components of this process.

The Role of Public Trust and Communication

Public trust is the cornerstone of a successful pandemic response. Open and honest communication about the risks of H5N1, the development and effectiveness of the vaccine, and the rationale behind distribution strategies is essential for building public confidence. Addressing concerns and misconceptions proactively, through clear and accessible language, is crucial. This includes transparently communicating about potential side effects and actively engaging with communities to build trust and address any hesitancy toward vaccination.

The involvement of community leaders and trusted voices can play a significant role in disseminating information and promoting vaccine uptake.

Vaccine Allocation Scenarios and Ethical Implications

The following scenarios illustrate the ethical complexities inherent in vaccine allocation:

Several different approaches to vaccine allocation exist, each with potential ethical implications. The choice of strategy requires careful consideration of multiple factors and a commitment to transparency and fairness.

- Scenario 1: Prioritization based on risk factors (e.g., healthcare workers, elderly, individuals with underlying health conditions): This approach maximizes the benefit by protecting those most vulnerable to severe illness and death. However, it may inadvertently disadvantage other groups, raising concerns about equity. For example, essential workers outside of healthcare might be overlooked, leading to disruptions in crucial services.

- Scenario 2: First-come, first-served distribution: This approach is simple to implement but can lead to inequitable access, with those who are better resourced or have better access to information benefiting disproportionately. This could exacerbate existing health disparities and leave vulnerable populations behind.

- Scenario 3: Equitable distribution based on population size: This approach aims for fairness by allocating vaccines proportionally to the population of each region or demographic group. However, it may not adequately address the needs of particularly vulnerable subpopulations within those larger groups. For instance, a remote community with a high prevalence of underlying health conditions might still face significant risk even with proportional allocation.

- Scenario 4: A lottery system: This approach promotes fairness by giving everyone an equal chance of receiving the vaccine. However, it might not prioritize those most at risk, potentially leading to higher mortality rates among vulnerable populations. Furthermore, it might not be viewed as legitimate or acceptable to the public.

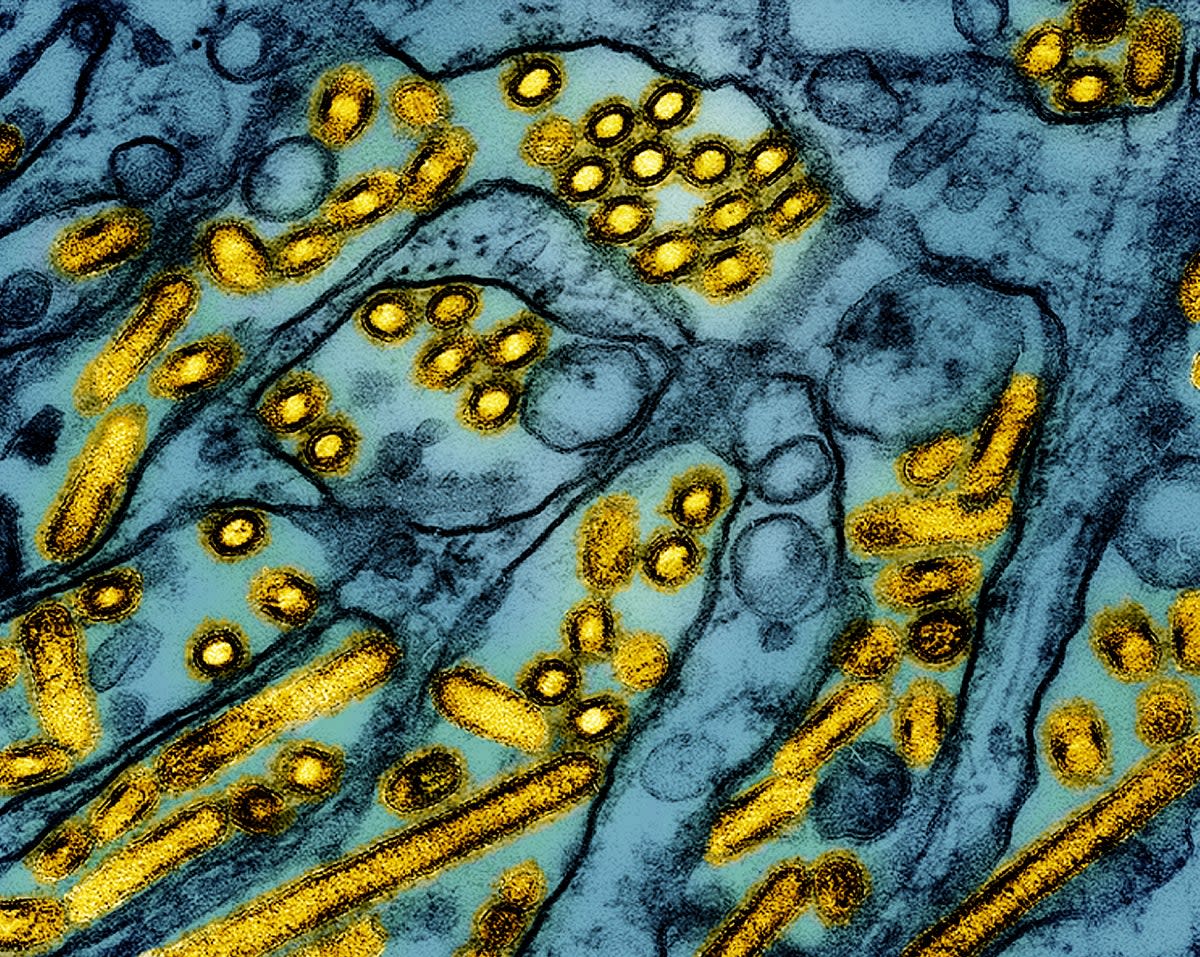

Visual Representation: H5n1 Alert Us Health Department Accelerates New Bird Flu Vaccine Development Amid Pandemic Scare

Understanding the structure of the H5N1 virus is crucial for developing effective vaccines and treatments. This microscopic pathogen, a subtype of influenza A virus, possesses a complex architecture that dictates its infectivity and virulence. Visualizing this structure helps us grasp its mechanisms of action and potential vulnerabilities.The H5N1 virus, like other influenza A viruses, is an enveloped virus with a roughly spherical shape.

Its diameter is approximately 80-120 nanometers. This envelope is a lipid bilayer derived from the host cell membrane during viral budding. Embedded within this envelope are two crucial surface glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). The genetic material of the virus, eight RNA segments, is enclosed within a protein capsid. These RNA segments code for the various viral proteins essential for replication and infectivity.

H5N1 Virus Structure: A Detailed Description

Imagine a detailed illustration of the H5N1 virus. At the center, we would see the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) core, a tightly packed complex consisting of the eight RNA segments, each associated with nucleoprotein (NP) molecules. These RNA segments are the virus’s genetic blueprint, carrying the instructions for producing all the viral proteins. Surrounding the RNP core is the matrix protein (M1), a layer that provides structural support and interacts with both the RNP and the viral envelope.Extending from the viral envelope are numerous spikes of HA and NA.

The HA protein is responsible for binding to receptors on the surface of host cells, initiating the infection process. The HA protein is a trimer, meaning three identical subunits come together to form a single spike. Each subunit has a globular head that binds to the host cell receptor and a stalk that anchors it to the viral membrane.

The HA protein’s structure determines the virus’s host range and is a primary target for neutralizing antibodies.The NA protein, also a tetramer (four identical subunits), is responsible for cleaving sialic acid from the host cell surface. This cleavage is crucial for the release of newly formed virus particles from infected cells, allowing the virus to spread to other cells.

Both HA and NA are important targets for antiviral drugs and vaccine development. The variations in the HA and NA proteins account for the different subtypes of influenza A virus, including H5N1. The lipid bilayer envelope itself is not directly encoded by the virus’s genome; it is derived from the host cell membrane during viral budding. This envelope’s fluidity is important for viral entry and release.

The entire structure, from the central RNA segments to the surface glycoproteins, works in concert to facilitate the virus’s life cycle.

Conclusion

The threat of a widespread H5N1 pandemic is a serious concern, but the rapid response from the US health department offers a glimmer of hope. The accelerated vaccine development process, coupled with public health measures, represents a proactive approach to mitigating the potential impact. While uncertainties remain, understanding the virus, the response strategies, and our individual roles in preparedness is paramount.

Staying informed and following public health guidelines are key steps in navigating this evolving situation. Let’s hope this proactive approach prevents a major crisis.

Query Resolution

What are the symptoms of H5N1 infection?

Symptoms can range from mild (like a common cold) to severe (pneumonia, respiratory failure). Severe cases often involve high fever, cough, shortness of breath, and muscle aches.

How is H5N1 transmitted?

Primarily through direct contact with infected birds (live or dead) or contaminated surfaces. Human-to-human transmission is rare but possible.

Who is most at risk from H5N1?

Those in close contact with poultry, healthcare workers, and individuals with weakened immune systems are at higher risk.

What can I do to protect myself?

Avoid contact with poultry, practice good hygiene (frequent handwashing), and follow public health guidelines.